What Does “ GOD ” Mean in Autonomous Driving?

In the field of autonomous driving for new energy vehicles, obstacle detection is a fundamental topic. But within this area, there’s a more advanced subfield — General Obstacle Detection (GOD). In this article, we’ll dive deep into what GOD means, how it works, and why it plays such a critical role in ensuring safety in autonomous vehicles.

🚗 Why Do We Need GOD?

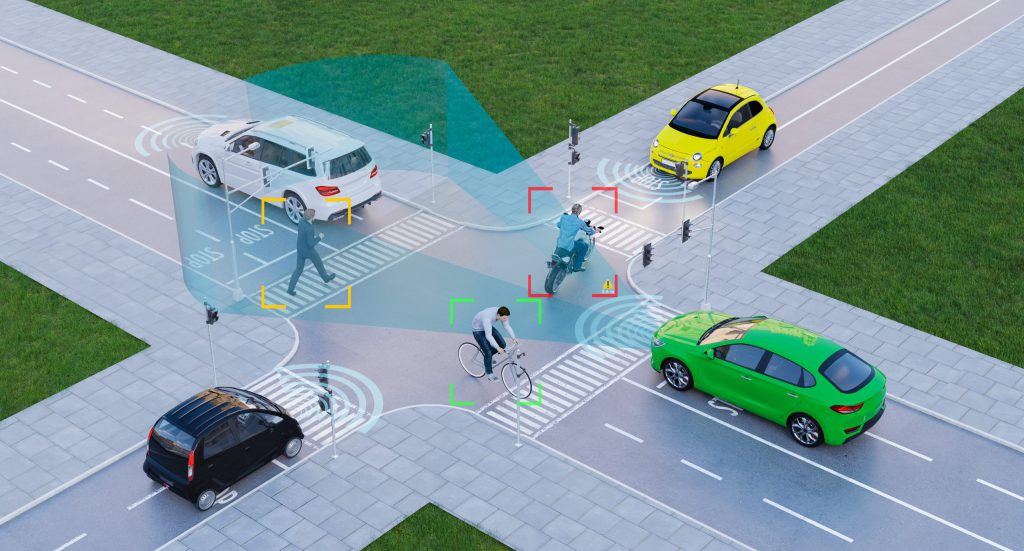

Traditional object detection systems can recognize only predefined categories such as pedestrians, vehicles, bicycles, or traffic cones. However, in real-world traffic scenarios, countless unpredictable objects can appear — a fallen cargo box, an overturned barrier, a large plastic sheet drifting across the lane, animals, temporary toolboxes, or even reflective debris obscured by rainwater.

All these items are “unknown” in terms of category, but for an autonomous vehicle, they’re real obstacles that must not be ignored.

The mission of GOD is to make obstacle detection universal. It must not only detect known object types but also identify unseen or abnormal objects that don’t exist in the training data. GOD’s output serves as a crucial safety input for the vehicle’s tracking, prediction, and planning modules.

Put simply, GOD doesn’t just answer “That’s a pedestrian” or “That’s a vehicle.” It tells you “There’s a solid object ahead that could block your path or pose a danger,” even under varying lighting, weather, and speed conditions. This capability is essential in complex urban traffic, construction zones, and adverse weather — where safety depends on recognizing not only the familiar but also the unexpected.

🧠 How Does GOD Work?

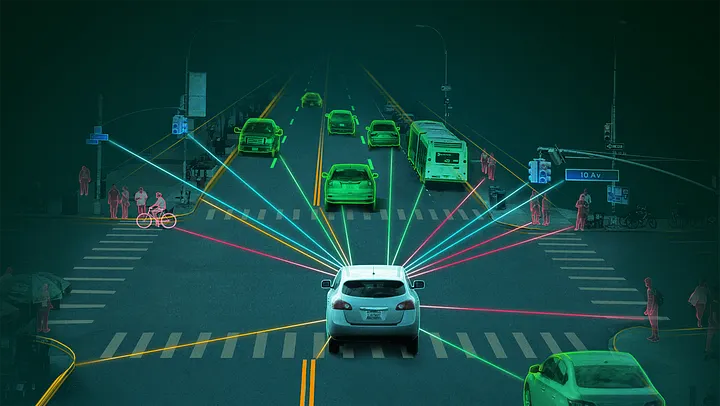

GOD systems take input from multiple sensors — mainly camera images and LiDAR point clouds, sometimes complemented by millimeter-wave radar or ultrasonic sensors. Cameras capture texture and color semantics, while LiDAR provides precise 3D geometry.

A practical GOD system fuses all these sensor streams and produces a unified set of candidate obstacles. Each obstacle can be represented as:

A bounding box, segmentation mask, or bird’s-eye-view occupancy grid

With attributes such as confidence score, speed estimation, class probability (if recognizable), and uncertainty rating

Many GOD frameworks build on existing architectures — using CNNs or Transformers for feature extraction, followed by detection heads to output bounding boxes and labels.

But GOD emphasizes two special capabilities:

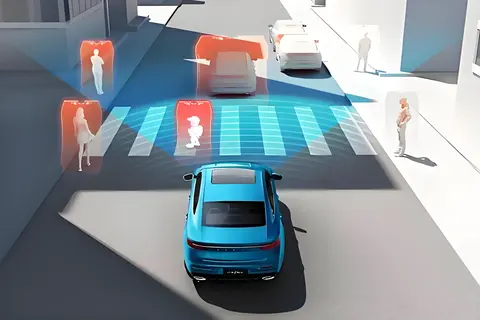

Open-set recognition — identifying objects it’s never seen before (“I don’t know what this is, but it’s dangerous”).

Robustness against small, transparent, reflective, or partially occluded objects.

To achieve this, GOD systems often integrate anomaly detection modules, geometric consistency checks (comparing LiDAR depth projections with camera detections), and temporal tracking to filter false positives or retain short-term occluded objects.

Time is another critical dimension. GOD doesn’t make decisions based on single frames; instead, it analyzes motion and consistency over time to ensure stable and reliable detection.

🔍 Core Technical Components and Implementation

GOD can be implemented using one-stage or two-stage detectors:

One-stage detectors (e.g., RetinaNet, CenterNet, FCOS) directly predict object positions and classes.

Two-stage detectors (e.g., Faster R-CNN) first propose candidate regions, then refine classification and localization.

Recently, Transformer-based models like DETR have been introduced, capable of modeling global context, though they still face challenges with computation cost and convergence.

Backbone networks must balance performance and efficiency. For visual inputs, models like ResNet, EfficientNet, or lightweight variants such as MobileNet and GhostNet are common to meet automotive-grade hardware constraints.

For LiDAR data, GOD systems may use:

Voxel-based 3D CNNs,

Point-based architectures (PointNet/PointNet++), or

Sparse convolution networks for higher efficiency.

To boost detection of unseen categories, GOD models often include anomaly or novelty loss functions, contrastive learning, or self-supervised pretraining to help the model learn the “normal world.” Objects deviating from that normal distribution are flagged as potential obstacles.

Training data is another key factor. Because real-world datasets rarely cover rare or abnormal cases, researchers expand training sets with synthetic scenes, rare event samples, and simulation-generated data. Data augmentation — occlusion, color shifts, lighting changes, or geometric distortion — further strengthens robustness.

Advanced systems even combine camera images with LiDAR depth maps under geometric consistency supervision to improve detection of transparent or reflective obstacles.

📊 Performance Evaluation of GOD

Traditional object detection uses metrics like mAP, precision/recall, and IoU. But these don’t fully apply to GOD.

In GOD, both false negatives and false positives carry safety risks:

Missing a box in the lane could cause a direct collision.

Frequent false alarms could trigger unnecessary braking, reducing ride comfort and creating rear-end risks.

Hence, GOD evaluation must include dynamic, safety-oriented metrics such as Time-to-Collision (TTC) and safety-critical distance, beyond static accuracy measures.

⚙️ Challenges in Real-World Deployment

Applying GOD to real vehicles faces several practical issues:

Sensor limitations: cameras struggle in low light or glare; LiDAR fails on transparent objects; radar lacks small-object resolution.

→ The solution is multi-sensor fusion, marking uncertain objects for continuous observation.Open-world uncertainty: real roads feature long-tail scenarios far beyond any dataset’s coverage. GOD must learn via unsupervised/self-supervised methods to model the “normal” world, flag anomalies, and rapidly adapt using meta-learning or few-shot learning.

Computational constraints: GOD must operate in milliseconds on low-power automotive-grade SoCs. Optimization techniques include model compression, quantization, operator acceleration, and priority scheduling (e.g., giving lane-keeping and front obstacle detection higher priority).

A well-designed GOD must also handle sensor failures or adversarial interference (like camera sticker attacks). Thus, degradation strategies are vital — when sensors or compute resources degrade, the vehicle must safely fall back to slower speeds, wider distances, or remote assistance.

🔄 Conclusion

General Obstacle Detection (GOD) bridges the gap between the open, unpredictable physical world and the closed, data-driven computation world of autonomous systems.

It isn’t a static algorithm, but a dynamic and continuously learning ecosystem — one that transforms every unknown and unseen real-world risk into a quantifiable form of uncertainty or anomaly.

The future of autonomous driving safety depends on GOD’s ability to perceive not just what it knows — but what it doesn’t.

Please explore our blog for the latest news and offers from the EV market.